An Iconography of Confusion: Why Map Portals Don’t Work, Part IV

“Why Map Portals Don’t Work” is a five-part exploration of why the dominant visual grammar of GIS interfaces serves its public audience so poorly and continues to diverge from the best practices found most everywhere else on the web. Read Part I, Part II, Part III, Part V. On February 27th, I will be joining James Fee for an online conversation about this series at SpatiallyAdjusted.com.

This being the season of penitence, let’s start with a confession. A few years back I had just finished prototyping my first geoprocessing web service and wanted to get some early feedback from likely users. So I approached a colleague with a PhD in Geology and, more importantly, significantly more zeroes in his bank account than you or I. I reproduce our conversation in its entirety:

HIM: [knitted brow, looking at my interface] What do you have going on here?

ME: [swelling with geodeveloper pride] On-the-fly buffering and intersecting tools!

HIM: What’s a buffer?

ME: [Exit stage left, muttering under breath]

The rest of that morning was filled with hard staring out the window pondering the vast gulf between what I thought was cool and useful and what an intelligent would-be user found confusing and, therefore, irrelevant.

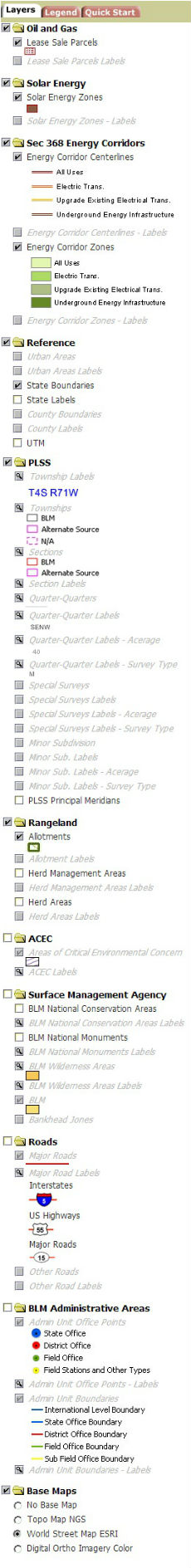

As we have learned from the City of Denver’s map usage statistics, the primary use of maps is quick information retrieval, NOT deep interaction with map interfaces. So toolbars filled with unfamiliar icons are not helpful. And toolbars with icons plus text descriptions are only marginally more so, because after all, “what’s a buffer?”

Users Do Interact With Hyperlinks, Info Balloons, and Hyperlinks Inside Info Balloons

As a core component of the visual grammar of the web, the text hyperlink is familiar to users. Further, due to the Google influence, people are familiar with clickable placemarks. And the Denver stats bear this out: over two placemarks are clicked per visit, and 12% of the time users click on hyperlinks inside info balloons. With this insight, you want to drive engagement with your map users right at the very start using a) a large, obvious auto-complete text entry box, b) placemarks that encourage interaction (e.g. zoom-to neighborhoods), and c) text-lists with hyperlinks.

Making users launch a “tool” or type into a non-responsive text box as a pre-requisite for map interaction is a recipe for rapid disengagement.

Ditch the “Identify” Tool

One of the main goals of any interactive map is to provide detailed information about features on the map. In traditional GIS desktop software, this is done using an “Identify” tool: click the tool, click on a feature on a map, and somewhere on the screen some attribute information will pop up. On a web map, the Identify tool is unfamiliar, time-consuming, and makes the critically wrong assumption that a user is interested in all of a map’s features equally. Once you elicit user intent–an address, a neighborhood, etc.–put clickable placemarks in that location and related locations around it. And use text lists of potential locations of interest: users can scan text much, much quicker than clicking placemarks. Again, there’s plenty to learn from Google Maps and Bing Maps and how they do map-based search for “pizza”, “coffee”, et al: a visual hierarchy of placemarks and a list dynamically refreshed as the user moves around the map.

UTF Grids, FTW

The greatest recent improvement in map interactivity has been the work Mapbox has done with UTFGrid (interactive demo here). Short version: each map tile has a compressed file of attribute info registered to its pixel space. As tiles get loaded into the interface, the attribute info is readily accessible just by the user mousing over or clicking on any location on the map. Ingenious! If your vendor doesn’t support UTFGrid (it’s an open specification), call your sales rep today and say your 1990s Identify tool has to go.

The Toolbar: the Wrong Tools for the Wrong Job

Icon-laden toolbars are a desktop thing, not a web thing. For web maps anything besides rapid search-and-retrieval of information is an edge case. And every second a user spends trying to decode your buttons and what they might do merely strengthens the resolve to leave your site.

—Brian Timoney

Addendum: Brian Flood noted on Twitter that Google has been using tiles + JSON to improve interactivity for a few years now (see example tile and JSON packet [text file download] ). Of course, no less credit to Mapbox for documenting and opening this approach.