The Tyranny of “Requirements”: Why Map Portals Don’t Work, Part III

“Why Map Portals Don’t Work” is a five-part exploration of why the dominant visual grammar of GIS interfaces serves its public audience so poorly and continues to diverge from the best practices found most everywhere else on the web. Read Part I, Part II, Part IV, Part V. On February 27th, I will be joining James Fee for an online conversation about this series at SpatiallyAdjusted.com.

Every IT project needs requirements, right? And “gathering” them sounds so collaborative, so collegial, and so relentlessly unobjectionable, what could possibly go wrong?

Besides your map portal project coming in late, over budget, and largely unusable? Nothing. Nothing at all.

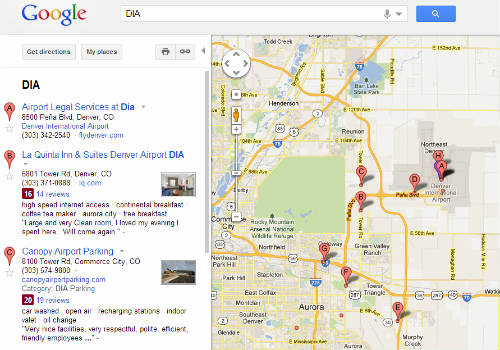

Because if you are building any public-facing interface you have exactly four requirements:

FAST • INTUITIVE • INFORMATIVE • FAST

Be clear on this single fact: you are competing for User Attention. On the Internet. You don’t get to set the rules.

But look on the bright side: you don’t have to write up Help documentation because normal people don’t read Help documentation. If they can’t figure out what to do—quickly—they simply you leave your site. The web is full of other interesting content that doesn’t need to be puzzled over.

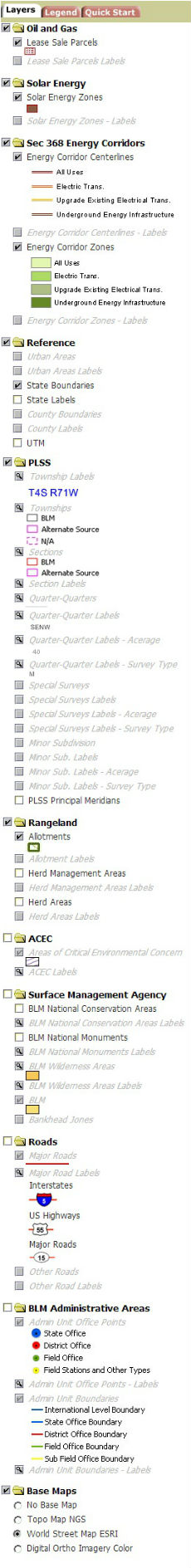

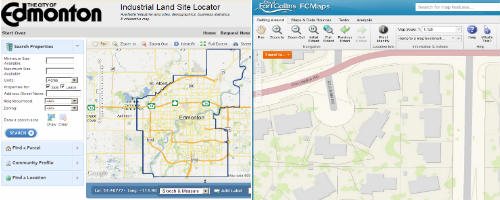

The Vicious Cycle of Bloat

Buying into the feature-laden, layers-upon-layers map portal paradigm quickly kicks off a vicious Cycle of Bloat. First, the portal gets a full menu of default features intended to serve both internal users as well as the general public. As layers and tools get added, it becomes necessary to hire a consultant/developer. OK, now our map portal is officially a Project. With your hired gun and extra coding fu at your disposal, adding a few more in-house edge cases doesn’t seem like a big deal (after all, you’re getting more value from your outside resource). And its Middle Management 101 to reach out to other departments to bring them on board if only to be able to spread the reputational blame around should things not work out as planned.

Too Many Engineers Spoil the UX

Playing a critical role in the Cycle of Bloat is our Engineering brethren. Specifically the subset of engineers who generously broadcast their technical criticisms with a cross-armed petulance gloriously liberated from ordinary self-awareness. That guy (yes, it’s always a guy), has his own laundry list of features—in-browser feature editing tools, map-composing options, and of course “print-to-plotter” are perennial favorites—without which he’ll unilaterally and loudly declare the whole thing a waste of money. All because of the obscure need for the map portal to do exactly what the $23,000 of technical software installed on his workstation already does.

The Power of No

The journey to clean, simple map interfaces geared towards the general public doesn’t start with a first step. It starts with a simple word.

No.

Saying “no” to the premise of a single map portal serving both internal users and the general public is the prerequisite to building anything that will meet the four non-negotiable criteria stated above. As someone famous once said, you can’t serve two masters—and neither can your map portal. Stop trying to build the mythical interface that’s all things to all people and you might just be able to pull off something that is worth the valuable time of your general users.

—Brian Timoney

** chefs photo courtesy of Wikimedia