The Massive Potential of Verizon Mapquest

Last week’s announcement of Verizon’s purchase of AOL (which includes Mapquest) was greeted mostly with attempts at humor, with references either to AOL trial offer CDs or the “You’ve Got Mail” movie. The first dozen entries were mildly amusing before the Law of Diminishing Returns reared its head.

Most of the analysis of the deal focused on mobile ad tech.

I know nothing about ad tech.

But I do know about maps, and from where I sit the ingredients are in place to make a combined Verizon Mapquest the most compelling value proposition this side of the Google geo empire.

* * * * * * * *

Ingredient #1: Mobility Data

Critical mass is 100 million US subscribers constantly pinging cell towers and generating spatially referenced information. And not just your location, but how you’re moving: we know that movement by auto can be distinguished from pedestrian activity and even bicycle activity. Sitting still in your office cube agonizing over lunch options can probably be inferred too.

Real-time traffic, crowd, and parking analysis leap to mind. But think about larger marketing issues. Customer segmentation based on zip code?

Please.

Our mobility patterns speak volumes about our consuming habits, and thin-slicing those habits (already being done by particularly data-savvy outfits) are going to be much more valuable when backed by Verizon-scale data streams than the coarse geographic aggregations of old .

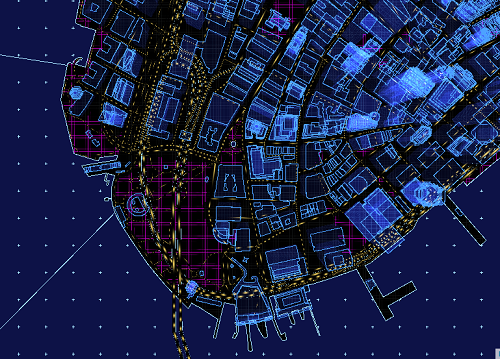

Ingredient #2: Advances in Map Rendering

Google turned the web mapping world upside down in 2005 when Google Maps gave us a slippy maps—the world as millions of 256×256 pixel tiles that loaded in the background to give the user an amazingly responsive experience.

But everyone got the same set of tiles.

Since then, newer approaches such as streaming vectors plus WebGL display technology mean that we are no longer limited to a one-size-fits-all map experience where everyone is looking at the same set of pre-rendered tiles. Instead, map features can be filtered, modified, and styled “on the fly” based on dynamic data. We’re all familiar with traffic overlays–imagine every feature on the map as modifiable based on user behavior and intent.

If you don’t follow the mapping industry closely, this bit can’t be emphasized enough: the tech is in place to usher in an era of “hyper personalization of maps” where you can tailor visual design to communicate so much more than a generic wayfinding experience.

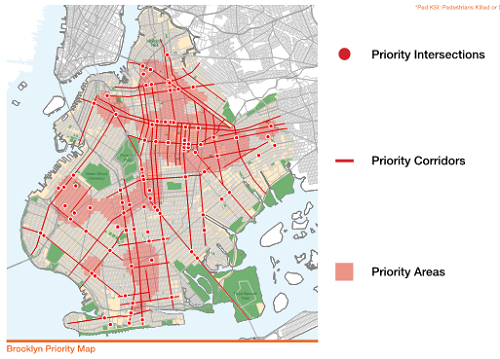

Ingredient #3: Noisy Mobile Data in Sufficient Quantity Becomes Valuable Spatial Data

No one should confuse their phone with a survey-grade GPS. But a fascinating complement to the explosion in data volumes has been the tools to aggregate and algorithmically smooth noisy data and transform it into useful spatial data. At Verizon-scale quantities of data, you don’t need a tricked out vehicle to survey the new subdivision to figure out where the roads are and how many lanes they have.

This is especially important now as the pending sale of Nokia HERE maps has highlighted the dependence on a small handful of base-map providers: Google, Tom Tom, Nokia Here, and Open Street Map (Mapquest currently uses Tom Tom and Open Street Map data). Sure, this data won’t be guiding self-driving cars (thankfully), but I can imagine real-time multi-modal mobility data being very useful for routing the emerging on-demand economy.

Ingredient #4: The Boring and the Obvious

Sales and support. Existing relationships with large customers. A phone number clients can call that will be answered by a breathing human being.

We all love cool tech. The blocking and tackling of everyday sales relationships? Probably less so. But having the sales infrastructure to go big? Safe to say we can check that box. What made the deal such a target of the Mocking Class was that AOL and Mapquest are so strongly associated with Web 1.0 (Mapquest is almost 50 years old, actually). But you know who doesn’t mind so much dealing with recognizable entities that have been around for decades? Other companies that have been around for decades and are not immediately stoked to cut huge checks to three year old companies missing vowels from their names.

If this blog has a unifying meta-theme, it’s that Technology is actually the easy part–it’s the Anthropology that’s really hard. Far be it from me to suggest the mere Bigness magically provides all the answers–but scale provides a sturdy safety net for the trial-and-error of determining which part of the cutting edge will work in the marketplace.

* * * * * * * *

From the outside it’s not clear what Verizon’s intentions are for Mapquest given the scant mention in the press. Whatever the case, the pieces are in place for the original web mapping company to shape the next generation mapping experience.

Brian Timoney is an information consultant in Denver, Colorado.