The Travelling Salesman Problem Is Not a Routing Problem, It’s A Monetization Problem

Creative destruction is awesome until it comes for your livelihood.

Having made a few dollars over the years building custom routing applications, I had two distinct reactions when testing out the Straightaway app recently after reading this Mapbox post.

“this is way cool and efficient” 😀

“time to look for another way to make money solving geospatial problems” 🙁

Of course routing has been firmly on the path of commodification since at least the Mapquest days in the late 1990s. When Google Maps came along with dynamic re-routing in the browser I was so delighted and befuddled I had to ask Brian Flood to explain to me (slowly) how this magic was happening.

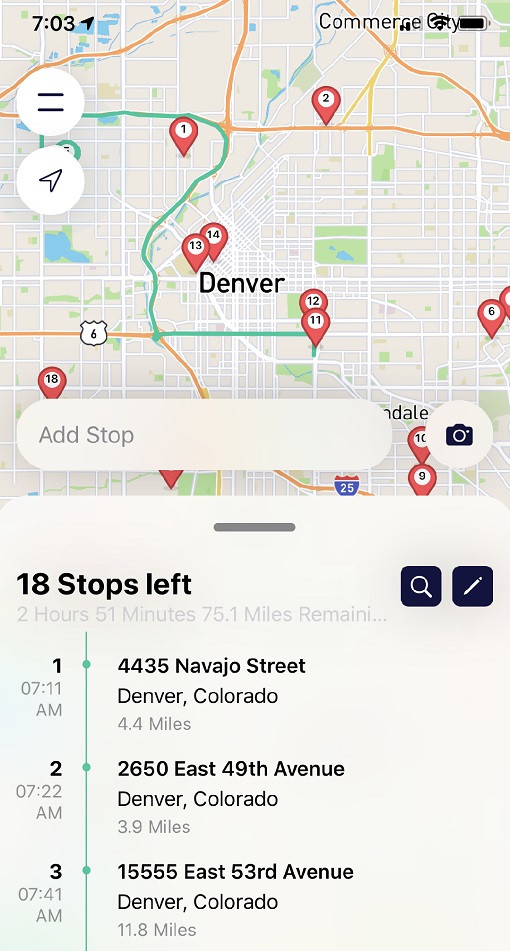

The app’s pitch is to optimize multi-stop delivery routes—the freemium version lets you route up to 25 stops, with some near real-time traffic awareness, and get an ordered set of stops with precise time estimates. But the real user-experience win is the OCR address detection of your list of stops using your phone camera! I printed out a list of 18 addresses spread around Denver and in a minute I had my detailed route.

* * * * * * *

What’s been the most valuable innovation in routing?

Hands down: turn-by-turn voice directions.

Without turn-by-turn voice directions, there is no multi-billion dollar gig economy of ridesharing and delivery because you would never have a critical mass of drivers if traditional map-reading skills were required (let alone their brute-force memorization a la “the Knowledge”). As geography enthusiasts, we wish that weren’t the case, but the World isn’t what it Ought to be (in so many ways).

Perhaps that’s the real lesson we should take away from a cool app that disrupts our Income Streams: spend more time thinking about UI/UX form factors that empower a broader audience rather than simply focusing on the geospatial wizardry that impresses our small in-group.

— Brian Timoney