Google Knew We Didn’t Want to Kill Spreadsheets. We Wanted A Billion Rows.

Study after study shows the negative health impacts of soda. And 7-11 has responded to market demand with a 128oz Mega Gulp.

For as fashionable as it is in the data community to feign exasperation with spreadsheets and the chaos they cause — mangling numbers and text, crimes against dates and times, relative vs absolute cell references, etc. — Google saw into our hearts and has granted our deepest unspoken wish.

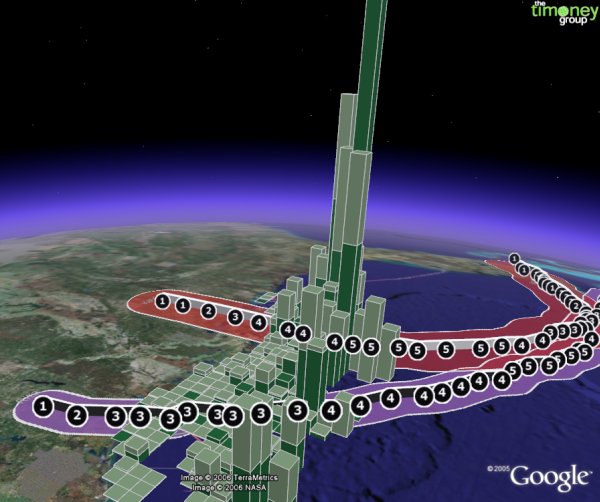

The billion-row spreadsheet.

Actually, it’s wiring up Google Sheets to BigQuery tables so the data doesn’t live in your spreadsheet per se (one good measure of disaster prevention!) but you can manipulate and analyze in a Google Sheet using standard tools e.g. pivot tables. As Ben Collins noted, the real win is doing work using these familiar spreadsheeting methods instead of writing SQL queries. Which is true, because SQL is a chokepoint.

“But everyone who works with data should learn SQL.”

And more Americans should learn a foreign language.

When asked how an adult may go about learning a foreign language, the linguist John McWhorter memorably replied “It’s hard. Sleep with somebody, frankly.” And while readers of this blog skew towards passionate lovers of data, willing to harness SQL for all manner of subqueries and cross lateral joins, the audience of those who merely want to shake hands with their data and answer a couple of questions is much larger.

Audience size and uptake–the key metrics we dismiss too easily. The spreadsheet is the signal achievement of the PC era and a three-decades track record of being the backbone of quantitative work. As any UI/UX pro knows, having millions of users willingly engage with an interface and its visual vernacular is very, very difficult. Despite its drawbacks, the spreadsheet is entrenched for good reasons and for the most part Familiarity Breeds Productivity.

Let’s warmly welcome the Billion Row Spreadsheet as another step forward in the democratization of quantitative analysis.

— Brian Timoney