Google Earth and the Quagmire of Enterprise IT

With Google Earth marking the 6th anniversary of its launch this month, the news that they’re going to throw their hat in the ring of enterprise data management has elicited some enthusiasm but also well-wishing. As in, “good luck with that.”

In a confluence that comes from too much web surfing, I saw the Directions Magazine Google Earth Builder webinar on the same day that Paul Ramsey pointed me to “Why businesses move to the cloud: They hate IT.” I made an analogous argument over a year ago: IT is suffocating GIS. Simply put, too many resources within GIS departments are devoted to sys admin tasks, database tuning, etc., instead of focusing on data accuracy, cartography, and spatial analysis. To be sure, this state of affairs benefits vendors collecting annual licensing fees: a colleague in Oil & Gas mentioned paying for three ArcServer licenses despite not having a chance “to play with it” yet.

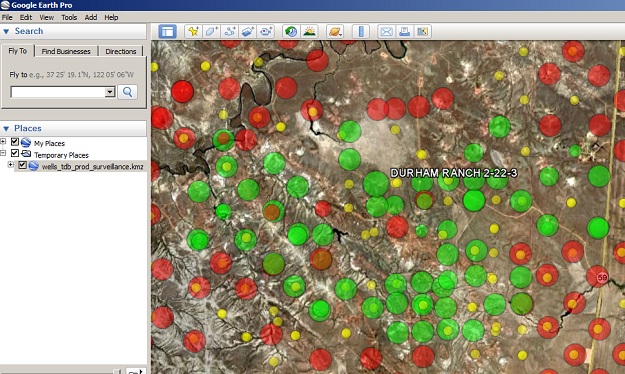

In important respects, Google Earth has always been “enterprise–ready” via the KML file format where with the <NetworkLink> and <Region> tags one can stream dynamically large corporate data stores all the day long. Add to the mix that both standard versions of Oracle and SQL Server ship with enough geospatial functionality for basic distance analysis and choropleth mapping and one can argue that with a little elbow grease, and a degree of internal coordination, much can be done with tools already in place.

But the internal coordination piece is the gotcha: technology is easy, it’s the anthropology that’s difficult. Nothing against human beings, but taking people out of the equation of organizational data flow is the biggest lure of Cloud platforms.

Can Google Earth Builder be successful? Sure: the big Federal agency contracts, the larger states, and the major extractive industries players can deliver the required returns. As for the medium- and small-fry, the more GIS-centric Cloud offerings from Arc2Earth and WeoGeo probably make more sense. Whatever the case, Google’s best hope lies not with the self-styled “visionary” CTO/CIO but rather those all too aware of the inertia and silo-ed intransigence inside their own organizations.

—Brian Timoney