Hopeful Developments In Government Data Publishing. Yes, I Said “Hopeful”

We’ve been talking Open Data for years here at MapBrief, often with a good deal of exasperation at the publishing priorities of otherwise well-intentioned government authorities.

But today I bring only hope.

Open With Apps – A Promising Syndication Model

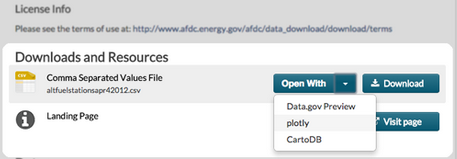

Back in March Data.gov announced “open with apps” where some datasets could now be visualized/analyzed directly using Plotly and/or CartoDB with the promise of more services being added.

Why this is good: it encourages a clean division of labor–government entities focus on data publishing while third party entities focus on visualization and analysis.

A credible, long-term commitment to open data requires resources. And diverting resources to one-off visualization tools has proved to be an enriching experience only for whatever government contractor built the thing.

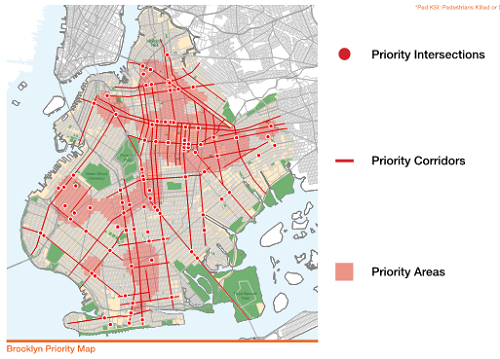

And mapping portals? Please, no more.

For a great read on why this single-minded focus data is so important, see this recent Chris Whong post .

Cloud Economics = Competing Platforms

Instead of handing millions to contractors for suboptimal interfaces, let the many cloud-based visualization platforms compete (‘compete’, in like, the capitalism sense of the word) to accept open data feeds and try and convert free-tier users to faithful subscribers through great user experiences.

Worst case scenario: none of these 3rd party platforms find it economically viable over the long run and open data publishers provide a download button and call it ‘done’.

Leave Infrastructure to the Experts

Another hopeful development is the announcement that Amazon is hosting Landsat scenes on its S3 infrastructure.

For free.

Again, the economics of the cloud are such that the experts can provide services at very low cost. Hence my plea awhile back that the government focus on data, not ‘infrastructure’. What we don’t need is a big contractor emulating the same service while soaking the taxpayer with a 15-20x mark-up.

* * * * * *

The Open Data movement has already won over those persuadable by the idealism of transparent government, etc. It’s been less successful articulating a nuts-and-bolts economic rationale. Here’s hoping the jettisoning of wasteful interfaces in favor of 3rd party syndication will encourage a singular focus on the data and nothing but the data.

—Brian Timoney