Why Map Portals Don’t Work – Part I

“Why Map Portals Don’t Work” is a five-part exploration of why the dominant visual grammar of GIS interfaces serves its public audience so poorly and continues to diverge from the best practices found most everywhere else on the web. Read Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V. On February 27th, I will be joining James Fee for an online conversation about this series at SpatiallyAdjusted.com.

It’s been six months since my most popular post How the Public Actually Uses Local Government Web Maps: Metrics from Denver; I’ve been gratified by the feedback. But despite laying out detailed metrics showing that single-topic maps garner 3x the traffic of traditional portals, that user-friendly text search is critical to the map experience, and that users don’t spend time fiddling with default viewer parameters, I’ve found two particular reactions troubling:

- No one has widely circulated their own web metrics that shine a more positive light on map portals.

- People still keep building public-facing map portals. And writing press releases about them.

For the next few posts, then, we’ll lay out some major drawbacks of standard web portals as well as suggest a few alternatives along the way. While the baseline scenario I have in mind are public-facing government mapping portals, those rolling corporate intranet solutions would do well to take heed.

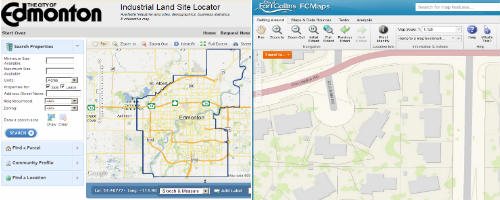

Problem #1: Map Portals Over-Focus on the Map, Under-focus on Text-Based Search and Discovery

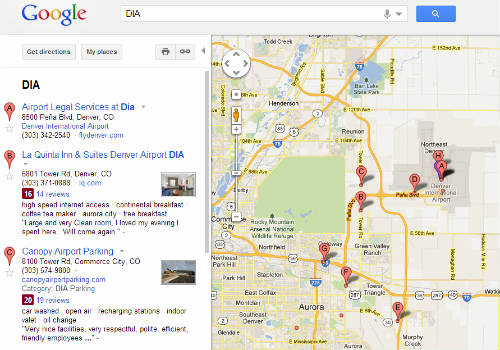

The dominant finding from Denver’s metrics is that the public approaches maps to retrieve particular bits of information, and then leave. And how does everyone do Search & Discovery? Think of your favorite search engine: you start typing into an auto-suggest box, then you get a text list of possibilities. Both Google Maps and Bing Maps use a similar visual grammar–search text-box across the top, listings on the left, map on the right.

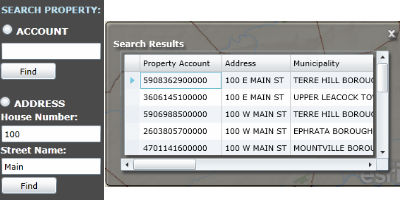

GIS people all-too-easily lose sight how unfamiliar map navigation is for the general user, especially when confronted with an “immersive” experience. The text box, then, featured prominently and with auto-complete, is a life-raft of familiarity. Contrast that to this typical setup that we find in the Lancaster County GIS Property Search site:

The search box is on the left side of the map, with Account search separate from Address search. OK, what’s an Account number? Address is familiar, but why is House Number separate from Street Name? Because, as we can all guess, that’s how it’s stored in the database. And none of this is auto-complete, so my address-lookup is really an address-guess. Being a clever sort, I enter “100” “Main” and get 15 possibilities popping up in a Results window on the other side of the map. And only two fields are clearly visible, the Property Account and the Address (which I already entered). Now this business with the Account number being featured so prominently is starting to make me wonder if this site is really meant for the public or the clerks in the Assessor’s Office who work with Account numbers all day long. Finally, instead of plotting the properties in the map as obvious, clickable placemarks, they’re rendered as polygons, which, at the zoom level necessary to encompass all 15 possibilities, makes them barely visible. Which I figured out when I went to remove a smudge from my monitor.

We’re not pointing fingers at Lancaster County here, because these are the same choices GIS people inflict on the public every day: unfamiliar interface layouts, text fields that don’t auto-complete, and results windows that pop up in other parts of the screen.

Takeaway #1: Users Want and Need a Large, Obvious, Auto-Complete Text Box to Drive Search & Discovery

Coming Soon: All Those Layers are Getting in the User’s Way

—Brian Timoney